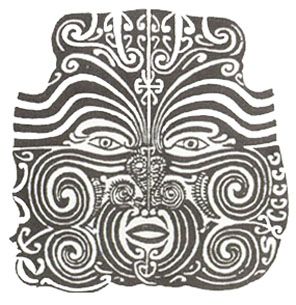

Moko

A moko is the facial tattoo of the Maori people of New Zealand. It is also a reference to a lizard found throughout Polynesia. Originally it was done to mark transition to adulthood for both men and women. Chiefs in New Zealand drew their moko as a signature on treaties, e.g. the maori language version of the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) has over 500 signatures of rangatira (chiefs), most of them are signed with partial moko.

Women wore smaller mokos on their chins and foreheads, whereas men wore full facial moko. Forced underground by colonial governments, moko was kept alive by women in remote areas and now ta Moko (Maori tattooing) is enjoying a resurgence among Maori today.

Kirituhi is another term for a Maori-style tattoo, one that uses Maori imagery but lacks any real cultural meaning, such as those that lack whakapapa or the long lines of genealogy which link all Maori at some point.

In traditional times, every line and koru (spiral) had a meaning and it was said that others could tell immediately which iwi (tribe) you were from upon seeing your moko. This inherent meaning in the lines and koru of moko is now all but lost, and most moko have a set basis from which they are worked. Most tribes still have tribe-specific designs which are used.

Moko were usually carried out by a tohunga-ta-moko (tattoo expert). Combs of bone were carved, sharpened, and affixed to lengths of wood.

Pigment was made from various vegetation like Kapia (Kauri Gum) or Mutara/Awheto, a caterpillar that mutates into a vegetable that is found on the floor of many native forests. As well as vegetable based pigments there was also a pigment made from dog feces called Awe.

As normal all natural materials were turned to carbon by way of firing, ground to a fine dust then mixed with a carrying agent, which was normally water to a fine fluid. [1]

The appropriate karakia (long religious chants) had to be recited by the tohunga in order for the moko application to be successful. The face would puff up and swell, but if the karakia was recited properly, then a beautiful moko would present itself once the swelling subsided. The moko looked deeply etched into the skin due to the incisions made.

With the coming of Pakeha (European colonisers, though the term today means the descendants of European colonisers), new materials were used for moko, such as metal needles which left a smoother appearance (as opposed to the etched look). This smoother appearance was sometimes seen as more desirable than the etched look, though the application of moko with needles was seen by some Maori as not being an authentic moko.

Moko is the most widely appropriated design in the world today when it comes to Western facial tattoos and the term "moko" is also appropriated. Being a taonga (treasure) of Maori, it is extremely offensive when moko has been appropriated by Pakeha (non-Maori NZers) and foreigners. The term "moko" should not be used for a facial tattoo that is not Maori. If one has not asked the permission of their whanau, hapu, and iwi (family, sub-tribe, and tribe respectively) then they have not gone through the proper channels before having it applied.

Being an intrinsic element of te ao Maori (the Maori world), moko signifies your dedication to your whanau, hapu, and iwi. It signifies your dedication to tikanga Maori (Maori custom and protocol), te reo Maori (the Maori language) and te ao Maori. It is not taken at all lightly, and is considered to be tapu (sacred). This is why misappropriation by Westerners is seen as a grave offense.

With this said, there is no reason why Westerners can't call their Maori-styled tattoo "kirituhi". It's simply not "moko".