Tissue Resorption

Over time, tissue may slowly be eroded by rubbing — this is perhaps both the largest and least known risk regarding implants. Imagine a fountain that slowly drips down in the same spot on its stone base over many years. Water, a substance far softer and more malleable than any implant, is able to dig deep holes through stone. Assuming you don't subject yourself to a secondary invasive removal procedure, what will an implant rubbing inside your body do after a decade or more? It will slowly, but surely, eat away at this tissue around it in a process known as tissue resorption. Gum recession from tongue and labret piercings is an example you are probably already aware of.

Resorption happens, to some extent, with all materials, but is minimized to negligible levels with soft, smooth materials such as cast silicone. In addition, the rate at which it happens varies from person to person — some people will get very little even from harder implants. Unfortunately, you can't take a test for your resorption potential. Also, because the implant is under your skin, you may not even become aware of this problem until it's too late if it's not in an area that causes functional problems — symptoms can take literally decades to show (although it is not unheard of for them to start showing within a month). Imagine implants on the forehead such as the fairly popular horn implants. The vast majority of these are done using hard materials such as Teflon domes. Unless you think you might be interested in a trepanation followed by a chunk of Teflon being pushed into your brain, you may want to reconsider that particular placement, or switching to softer silicone ... Not that the other common placements are safer — it's probably obvious the long-term crippling damage that could be done if an implant is placed on the top of a hand.

These risks are also an issue over softer muscular tissues; over time, the layers protecting the muscle can be eroded, and the implant can begin sinking into the muscle. I recently observed a case where a long single-piece vertical implant was placed between the sternum and the navel. Naturally, every time this person bent over, the bottom of the implant tried to bury itself into the muscles above his navel, wearing down the body's natural defenses. This person now experiences radiating pain around the implant and has lost some mobility, and is of course seeking medical assistance in the implant's removal.

This risk can be minimized both by choosing safe locations and by using a soft, smooth implant material such as cast silicone.

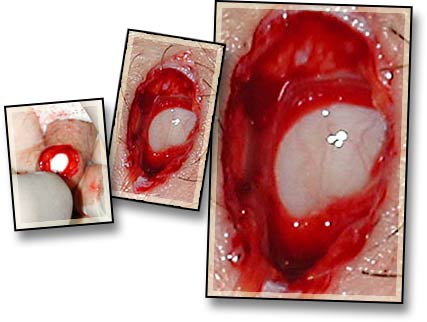

The photo above and to the left shows a teflon dome implant located centrally on the sternum being removed. In the others, the white tissue is the bone and cartilage which has been partially eroded and totally exposed. This implant was removed at eight months old and was done by the one of the most recommended and experienced practitioners.