Surface Piercing Rejection

Most of the time when small objects are placed under the skin, your body pushes them out like a splinter. To simplify, this happens by "selective suicide", where the skin above the object dies, and it falls out. In the case of a piercing, this happens from the outside edges in, as seen in the animation to the right, and as I've marked with red in the diagrams. This happens almost automatically as the object (jewelry) disrupts the natural living processes of the cells affected. This is especially true for surface piercings (see the section on surface bar jewelry for a bit more information).

Surface piercings will only fully heal when it is easier for your body than pushing the jewelry out. By making it "difficult" by both asking the body to sacrifice "too much" tissue, by doing as little damage with the piercing as possible, and by minimizing the body's immune response, this rejection process can be frozen, but it is still very important to note that chances of rejection decrease when using a skilled, experienced piercer for the piercing. Surface piercing rejection is a natural consequence if performed by an inexperienced piercer.

It is important to note that a piercing always sits on this balance -- it never leaves. If you bump a well healed piercing even years after having it done, and cause enough damage to tip the scales, a rejection process will start. Once started, rejection processes are effectively impossible to stop.

Contents |

Examples

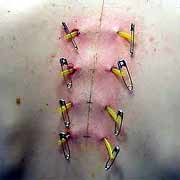

To illustrate more thoroughly, included are a few piercings from BME and why they failed (or will fail). Apologies to the clients and piercers involved for "outing" them, but the fact is that these are poorly done piercings:

Contributing Factors

- Up-pressure - The jewelry exerts leverage up on the skin above it. This stresses the tissue, and also partially clamps off blood supply to it.

- General damage - The process of doing the piercing damages the tissue and weakens it, initiating the healing/rejection process. In addition, the continual damage caused by light allergic response to the jewelry can irritate surrounding tissue enough to cause rejection.

- Motion - If a piercing is placed in a location that moves, either by twisting, stretching, or compression of the skin it's through, forces will be applied to the entire piercing, including the entrance and exit holes.

- Impact - If a piercing is placed in a location that regularly gets bumped (not just by accident, but also by things like clothing and belts), this can of course damage the piercing.

- Drainage - In the process of healing, dead tissue (both from the area, and the corpses of cells sent to help heal) is thrown away and replaced with healed tissue. The body must have a channel for disposing of this waste to effectively heal.

Reducing the Factors

- Up-pressure - There are a few overlapping routes to minimizing this:

- Placement - Some skin is tighter than others. Some looser skin, either because of its anatomical placement, or because of the age of the client, is very pierceable, even with poor technique.

- Jewelry Material - A jewelry's ability to conform to the body's needs goes a long way to stopping rejection, but doesn't entirely eliminate the problem. Using this route to stop rejection, metals are horrible, nylon is only marginally better, and Tygon is the current champion of this method.

- Jewelry Shape - Careful jewelry design can effectively totally eliminate up-pressure issues if the jewelry passes straight down to a "safe" distance, moves across the skin at a consistent depth, and then re-exits straight up again.

- General damage - Normally the damage shouldn't be a major issue, but realize that it's at the entrance and exit points of the piercing that any rejection will occur, so don't give it an excuse. The piercing should be cleanly done and as much as possible follow the precise path of the jewelry. As far as material, the material that causes the least response from the body should be used -- in general this means titanium, as well as some plastics.

- Motion - Draw a grid on your skin, and draw the piercing on your skin over the grid. Now, move the area as much as you can. For the piercing to be viable, this line should stay constant in shape and length, no matter what position the body is put in. Flexible jewelry will give you more freedom as far as motion, but ideally this problem should be solved with careful placement.

- Impact - If you put a piercing on your hands, your forearms, your shins, or any number of other places depending on your lifestyle, you're going to hit it on things a lot. There's nothing you can do about this outside of not putting piercings in these locations. In addition, if you know that a bra strap or belt will rub on the piercing, that alone is often enough to make it fail.

- Drainage - A piercing of a given gauge has a maximum length, with larger jewelry being able to support longer lengths. Realistically, keep surface piercings to under two inches in length.

First of all, all people heal differently. Some people are able to heal piercings even if they violate many of the suggestions above. In other people the piercings may appear "healed" for months before showing problems (and if they take out the piercing before then, they'll swear up and down that it was healed forever). Point is, most people who drive drunk get home safely without killing anyone, but that doesn't make it a good idea.

Piercing Techniques

Here are a few of the techniques people have used to try and make surface piercings heal:

- "Traditional" technique - Ignoring the morons that pierced (and still pierce) surface piercings like they would an ear, traditionally surface piercings were done with either curved barbells or nylon bars. While these do heal in a small percentage of people, they are almost all unsuccessful in the long term. This method is unacceptable, and any piercer performing it should be avoided.

- Scalpelled Surface Piercing technique - This technique is probably the only serious method that attempts to allow people to perform surface piercings using traditional metal jewelry. The theory is to create a low-pressure "flap" that the jewelry will sit under and have minimal interaction with. Unfortunately, the body tends to "pull down" the tissue quite quickly on most people, simply slowing down rejection rather than eliminating it. In any case, this is an experimental technique that is not available to the general public. This technique has been largely superseded by the punch and taper method and surface bars.

- Scar-and-brace piercing techniques - Some people experimented with piercing underneath a brace, either toughened tissue or a small implant. Unfortunately this tended to lead to other complications, and this techncique is rarely pursued except as a novelty.

- Surgical Techniques - Transscrotal Piercings and Bipedicle Flaps are good examples of this method (which isn't technically piercing anyway). The aim is for a single procedure to leave the client with a well developed fistula ("skin tube") by surgically constructing it. This technique is well out of the reach of all but a handful of piercers and should not be generally even considered.

- Flexible Jewelry (Tygon) technique - Tygon is a flexible inert plastic tube that has become quite popular in surface piercing. It is far more flexible than nylon, and thus greatly reduces the pressures that the piercing puts on the skin. If you are going to use any technique other than surface bars, or want to do a surface piercing in a location not suited to surface bars, this method is the most likely to work, but still less reliable than using surface bars.

- Surface bars - Surface bars are generally thought to be the single best -- and perhaps only -- acceptable solution for most surface piercings. They attempt to solve the problems in surface piercing by intelligent jewelry design.

- Punch and Taper - This is a newer technique used in conjunction with a surface bar to ensure the path made for the jewellery is exactly the same shape as the jewellery itself, resulting in shorter healing times and reducing the risk of rejection.

See Also